The importance of land acknowledgments

August 11, 2021

A land acknowledgment is a formal way to recognize the Indigenous peoples who have come before you, and who were removed — often violently — from their land due to colonization.

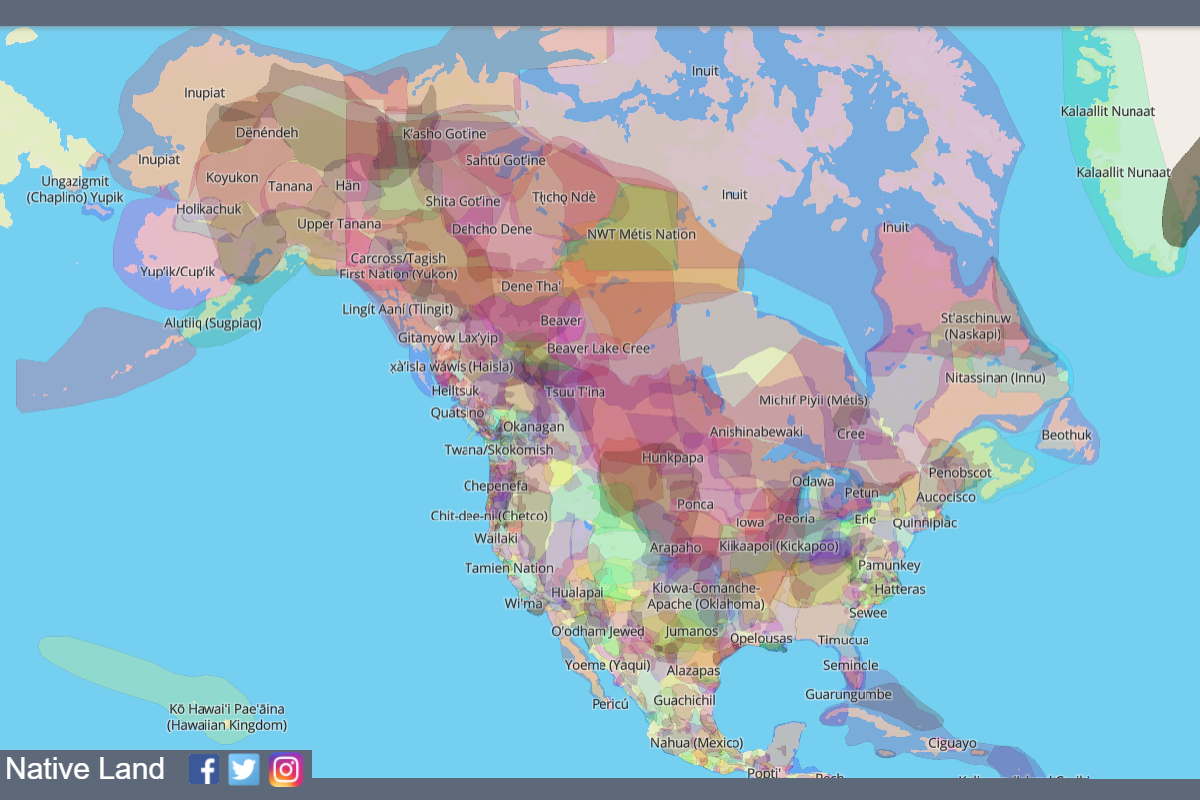

Cover: Interactive map via Native Land Digital.

By: Kayla Heidenreich

I, Kayla Heidenreich, have written this on the traditional lands and territories of the Indigenous Nooksack and Coast Salish Tribes.

Alaska Wilderness League recognizes that our offices are located on the traditional territories of the Dena’ina (Anchorage), Anacostan (D.C.) and Piscataway (D.C.) peoples and acknowledge the land stewardship and place-based knowledge of the peoples of these territories.

What is a land acknowledgment?

A land acknowledgment is a formal way to recognize the Indigenous peoples who have come before you, and who were removed — often violently — from their land due to colonization. It is a way to acknowledge the vital relationship between Indigenous peoples and the land while recognizing that these people still exist and practice their cultures today. Land acknowledgments are one small way to bring to light treaties and broken promises. It’s a way to start speaking out against the genocide, cultural appropriation, and all the other wrongdoings we have done to the Indigenous peoples of North America.

There are many ways to conduct a land acknowledgment, and it starts with researching who’s land you are living and recreating on. Using websites such as Native Land Digital and Whose Land are great places to start. Combining good intentions with correct information is the perfect way to create a good land acknowledgment.

Why are land acknowledgments so important?

Land acknowledgments are not meant to be a strict word-for-word requirement, they are meant to be done out of respect. They are meant to have education behind them. Colonization has displaced and killed Indigenous people across the globe who have existed since time immemorial. Today, these people still face the traumas of colonialism.

The Gwich’in people of Alaska and Canada have been fighting for decades to save land sacred to them in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and their way of life from detrimental oil drilling. The Western Shoshone people of Newe Sogobia (unceded land extending south from western Utah and eastern Idaho through the eastern half of Nevada and into the Mojave Desert in southeastern California) are considered the most bombed nation on earth due to the 900+ nuclear tests that have been conducted by the U.S. government on their sacred land. The Washoe Tribe of Da ow aga (Lake Tahoe) are fighting to change the extremely derogatory name of the Squaw Valley Ski Resort in northern California — the term “squaw” has historically been used to describe Indigenous North American women and is considered offensive, derogatory, misogynist and racist.

These people are still being oppressed. Land acknowledgments begin the process of taking responsibility for the harm colonization has implemented on the continent’s first peoples and help us become allies to these people.

How can our future benefit from learning about land acknowledgments?

Making land acknowledgments more customary is an important step we need to take. Land acknowledgments should be taught and conducted in schools starting in kindergarten and continued throughout our education system. Making this information accessible to teachers can help them provide students with a richer and more accurate picture of our history and the history of our continent, and the impacts of colonization on the Indigenous peoples already inhabiting these lands.

Indigenous people have coexisted with the land since time immemorial and, especially in this time of climate change and environmental destruction, there is much we can learn from their traditional knowledge. Land acknowledgments open the door to allowing kids to learn new ways to better coexist not only with each other, but with the entirety of the planet.

“Getting to know people, creating a relationship to the place that you are from, the water that you drink…getting to know these things in an intimate way, is what essentially, will change people’s minds, change people’s hearts. Acknowledging the land and water that sustains us and life on Mother Earth is part of becoming a balanced and present human being. It’s about honouring and protecting the land and water, honouring ourselves and our bodies.”

–Nigit’stil Norbert, Gwich’ya Gwich’in, born and raised in Denendeh, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories (via Whose Land)

If you’re interested in learning more, you can check out a link to a lesson plan I have created to help incorporate these lesson plans into schools.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by Alaska Wilderness League. (Although spoiler, in this case we definitely do! –AWL)

Kayla Heidenreich is from Bellingham WA, traditional lands and territories of the Coast Salish and Nooksack Tribes. She is a recent college graduate living with her cat Meatball out of her refurbished school bus, finding ways to raise awareness for Indigenous rights and environmental justice.

Kayla Heidenreich is from Bellingham WA, traditional lands and territories of the Coast Salish and Nooksack Tribes. She is a recent college graduate living with her cat Meatball out of her refurbished school bus, finding ways to raise awareness for Indigenous rights and environmental justice.