An Arctic Fourth Of July

July 8, 2016

The following was written by Alaska Wilderness League Guardian Tom Anderson on his Aligning With Nature blog.

Posted July 2nd, 2016. Written by Tom Anderson.

A year ago today four of us were heading down an Arctic river on a “freedom float.” For nearly a month we paddled the Utukuk River in Alaska to the Chukchi Sea at the southern margin of the Arctic Ocean.

For most of the 200 miles of paddling and hiking we felt the aloneness but not the loneliness of the vast arctic tundra. Formally known as the Naval Petroleum Reserve, this piece of real estate is the size of Indiana and has only a few native villages within it. No freeways, nor roads connecting anything other than some streets within the villages.

President Harding established the Reserve in 1923. At that time the U.S. Navy was transitioning from coal-fueled ships to those that would run on petroleum. Personally I get a nervous tick when I find the word “petroleum” used in the description of a wilderness area.

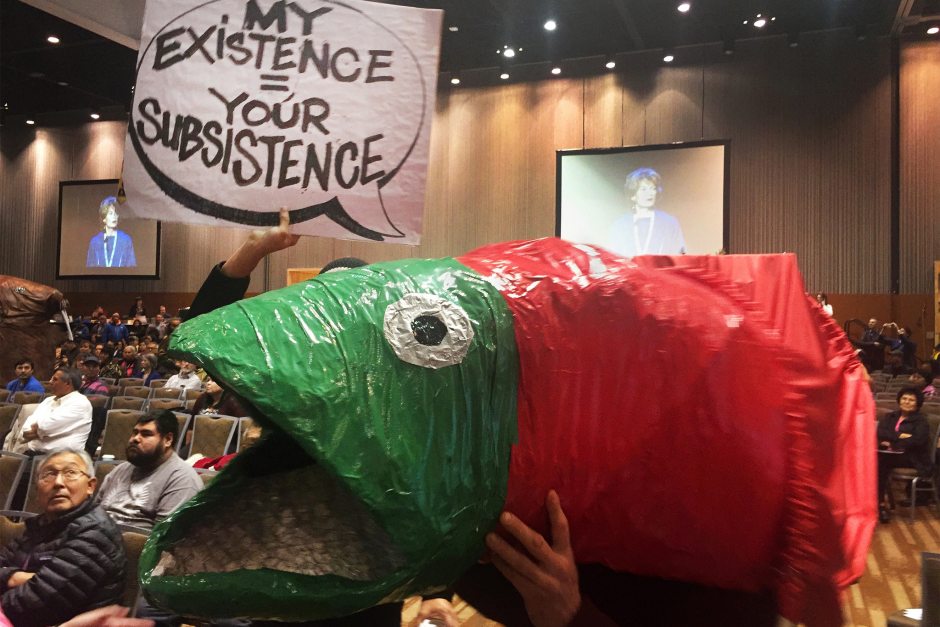

According to the Alaska Wilderness League, “the Reserve includes some of our nation’s most vital natural resources – millions of acres of wilderness-quality lands with critical habitat for migratory birds, brown bears, caribou, threatened polar bears, walrus, endangered beluga whales and more. The Alaska Native communities that live along the Reserve have maintained a subsistence lifestyle for thousands of years based on the Reserve’s living resources.”

This is a land where the river braids and snakes its way like endless ribbons of silver, off the north slope of the Brooks Range. This mountain range, over 700 miles long, is the largest in the world above the Arctic Circle. The Utukuk snakes its way out of the naked foothills onto the “arctic prairies” of the coastal plan.

This unrestrained landscape is home to the Western Arctic Caribou herd, over 400,000 animals. We missed by mere days the main passage of migratory herds as they pushed over the river heading to the coastal plains where calving would take place. Tracks and worn trails were everywhere.

It’s only natural that predators follow this moving meat market. We saw 10 grizzly bears, a handful of wolves and abundant golden eagles.

Daily we “oohed and aahed” at the blessedly mute floral fireworks. Hudson Bay Company agent and explorer Thomas Simpson explored the arctic coast from 1836-39. In his journal he referred to the arctic landscape as “party-colored” as it is crowded with stunted arctic flowers. Short in nature, their colors boldly but silently beg for the attention of pollinating insects.

Arctic lupines and tiny saxifrages provided purples. Bursts of bright yellow quivered in the arctic poppies and draba. I loved the cushions of pink displayed in moss campion. In some places the bell-shaped white flowers of arctic heather grew so dense that the land appeared snow-covered.

On July 3rd, we finally got to the 125-mile long Kasegaluk Lagoon. The lagoon is home to nearly 4,000 beluga whales, over half the world’s Pacific black brant population and scores of other species of waterfowl and shorebirds, not to mention walrus, seals and polar bears. Although the lagoon was designated a “special area” in 2004 restricting all oil and gas leasing for ten years, there is no permanent protection.

Two Inupiat communities are located at each end of the lagoon. Their combined population of less than 800 people depends on the lagoon and adjacent lands for their grocery store, as they are very much a subsistence population. Freedom for these Inupiat is found in the life-rich, healthy waters and the quiet, vast landscape that provides their sustenance.

Back in the 1970s, while nearing the end of a long canoe trip in Canada’s Northwest Territories, we were surprised to hear a motor approaching our camp. A three-wheeler was carefully wending its way across the tundra. The young Inuit man pulled up, smiled and shyly got off his machine to talk with us. English was clearly not his first language.

Predictably, when one falters in trying to find meaningful dialogue with a stranger, we fall back on the predictable query and we asked him, “What do you do for a living?”

He looked confused in response to the question but then hesitantly explained, “Why I hunt. I fish. I live.”

Before he drove off, he unwrapped a good-sized portion of a fresh caribou quarter and gave it to us. With a smile and a timid wave he drove off over the seemingly infinite landscape. We stood quietly watching and suddenly became aware of liberties unlike anything we had ever experienced.

When I participate in wilderness living, my ego is set aside and the jangles, rings, roars and squeals of civilization are absent. I am gloriously made small so that I might better take in great quaffs of real freedom.

I have had the privilege, yes, and the freedom and means to indulge in paddling several thousand miles of remote, wilderness rivers. Here in this quiet land we can forget keeping time and live simply. Here our actions are ruled only by moments of hunger or need for sleep.

But on each wilderness trip, I have felt the shackles of schedules. We had to paddle to a certain point at a particular date to get picked up so that we could make our way back to our civilized homes where we would engage in a litany of work and life schedules.

It’s absolutely true that as a consuming being, I am dependent on the noises of commerce. However, I periodically need to check into the wild for an adjustment to my soul. It is here that I experience raw, unabashed joy and taste real freedom.

If I fly a fly a flag patterned with stars and stripes am I a greater patriot than one who sacrifices and toils for a healthy land?

I would argue that poisoning and ravaging our soils and waters is an act of terrorism that threatens services that allow you and I to live healthy lives. Any act to minimize that threat should be recognized as heroic as it secures a greater likelihood of a safer and vigorous tomorrow.

After two days of paddling the brackish waters of the long lagoon, we pulled our canoes up to the Inupiat village of Point Lay. It was the 4th of July. After securing permission to set up our two tents on the beach below the village, we were invited to a celebration feast and drum dance. It mattered little that we were strangers or looked different from almost all 189 residents of the community.

Excited to perhaps eat local cuisine such as beluga, caribou, or seal, I have to admit feeling disappointment when we discovered tables covered with platters of hot dogs, burgers, salads, chips and even apple pies. It seemed wrong that most of this food was flown in thousands miles. But then I realized that much of the food I eat in Minnesota makes a similar long trip to get to my plate.

A single four-wheeler decorated with twin clusters of balloons and a flag made up the shortest parade I have ever seen.

And that evening under the midnight sun, residents of all ages listened to the seated drummers and danced stories of ancient times. We were mesmerized by the subtle and demonstrative movements that spoke of walrus hunts, kayak paddling, celebrations and other tales foreign to our repertoire. But that didn’t stop the locals from beckoning us out onto the floor to joinnin their dance. While we moved with little of the grace that we had witnessed our efforts inspired scores of smiles.