Little-Known “D1” Lands Protecting 28 Million Acres in Alaska Under Threat

In 1971, President Richard Nixon (surprisingly enough) passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which at the time was the largest land claims settlement in U.S. history. One of the most impressive features of the bill was section 17(d)(1) which gave the Interior Secretary the authority to set portions of that land aside to be protected for subsistence ways of life, cultural relationships with the land, and protection for wildlife.

This might seem like a lot of policy technical jargon but basically thanks to section 17(d)(1) — or D1 for short — the Secretary of the Interior was able to set aside about 57 million acres of this land so that it would be protected from fossil fuel and mining extraction.

For the last 50 or so years, that land remained set aside, ensuring Indigenous communities’ ways of life, safeguarding the landscape from the irreversible destruction of extractive industries that popped up all around Alaska.

Though it was never a guarantee, for many decades it seemed as though this land would remain protected, off the table to oil and gas exploration and mining extraction in perpetuity. However, in 2020 under the Trump administration, former Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt began pulling that safeguard apart.

From October 2018 to June 2019, Bernhardt opened more than 1.3 million acres of this land to mining, with the only public notice coming through a Federal Register announcement — an un-inclusive process leaving out Americans’ voices on the issue.

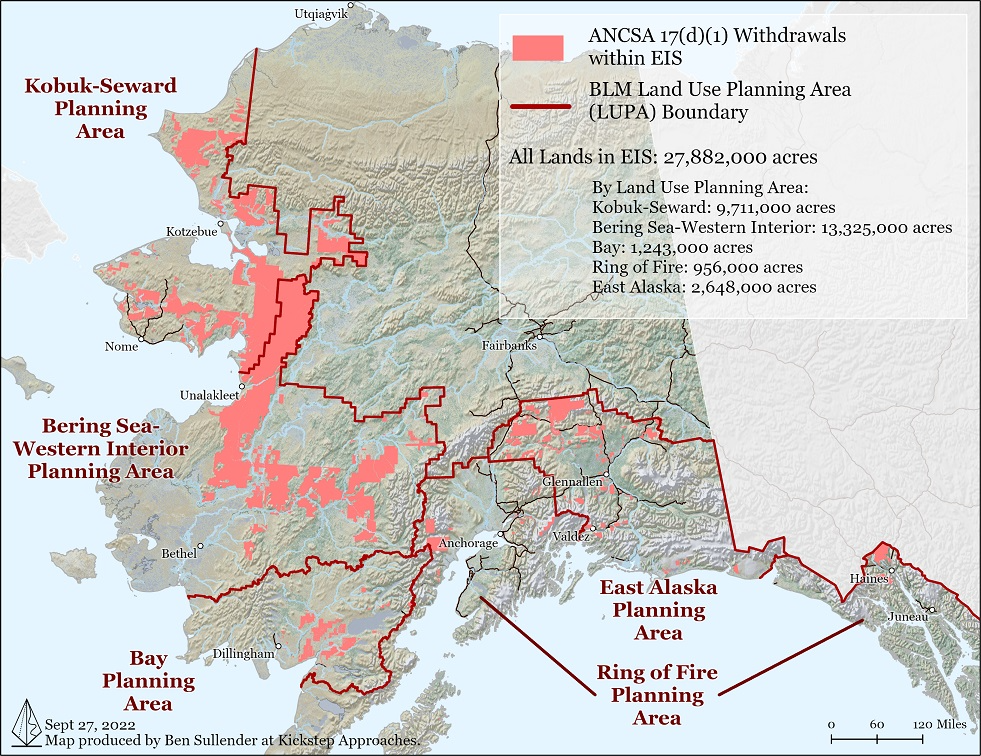

He quickly turned his eye to another 28 million acres through five Public Land Orders (PLOs) — which basically allow the Secretary of the Interior to implement, modify, extend or revoke land withdrawals under the authority of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA)— across the Bay, Bering Sea-Western Interior, East Alaska, Kobuk-Seward Peninsula and Ring of Fire planning areas.

Thankfully, these five PLOs never went into effect, and under the Biden administration, it was determined they were in fact legally flawed. However, they were unfortunately never formally rescinded and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) — the agency that manages these lands — has again issued a notice of intent to consider opening them to extraction.

If BLM opens this land, it will become one of the largest openings of public land to extractive industries in U.S. history. But worse, it would become MUCH more difficult for a future president to reverse this decision and return protections.

The tiniest silver lining is that processes are slightly different this time around and the administration is interested in hearing from the public before making their final decision. On December 15, 2023, BLM opened a formal 60-day comment period on the environmental impact statement (EIS).

One of the incredibly unique aspects of this piece of land is that it covers great swaths of migration corridors, connecting portions of the state and covering nearly 13 percent of Alaska and representing some of the nation’s last remaining intact ecosystems. Most importantly, these lands hold an incredible number of cultural, subsistence and ecological values that Alaska Native peoples have relied on for millennia.

With the window for comment to protect these 28 million acres from extractive destruction closing on February 14, 2024 — the loveliest of days — it’s a critical time to submit as many comments as we can to support the Biden administration and urge them to choose the no action alternative, leaving protections for 28 million acres in place.