Home from the Range

In the heart of northern Alaska, the threat of a devastating development project has hung over wild landscapes for decades. The proposed Ambler Road would be a new, 211-mile industrial corridor on the south side of the Brooks Range, extending west from the Dalton Highway to the south bank of the Ambler River.

Not just a mere road, Ambler would be a massive industrial corridor that would threaten North America’s largest protected and roadless region, as well as the food security and clean water of Alaska Native Tribes. The project would destroy more than 1,400 acres of wetlands and cross nearly 3,000 streams. It would cut through Gates of the Arctic National Preserve, across sheefish and salmon spawning habitats, and bisect the migration of one of the greatest caribou herds left on Earth. The purpose of this road is to eventually develop multiple open pit copper mines, threatening fisheries of the Kobuk and Koyukuk rivers and other traditional subsistence resources that locals depend upon.

Read on below to hear from author and League supporter Michael Engelhard about this special region, and why he feels we should protect it.

Home from the Range

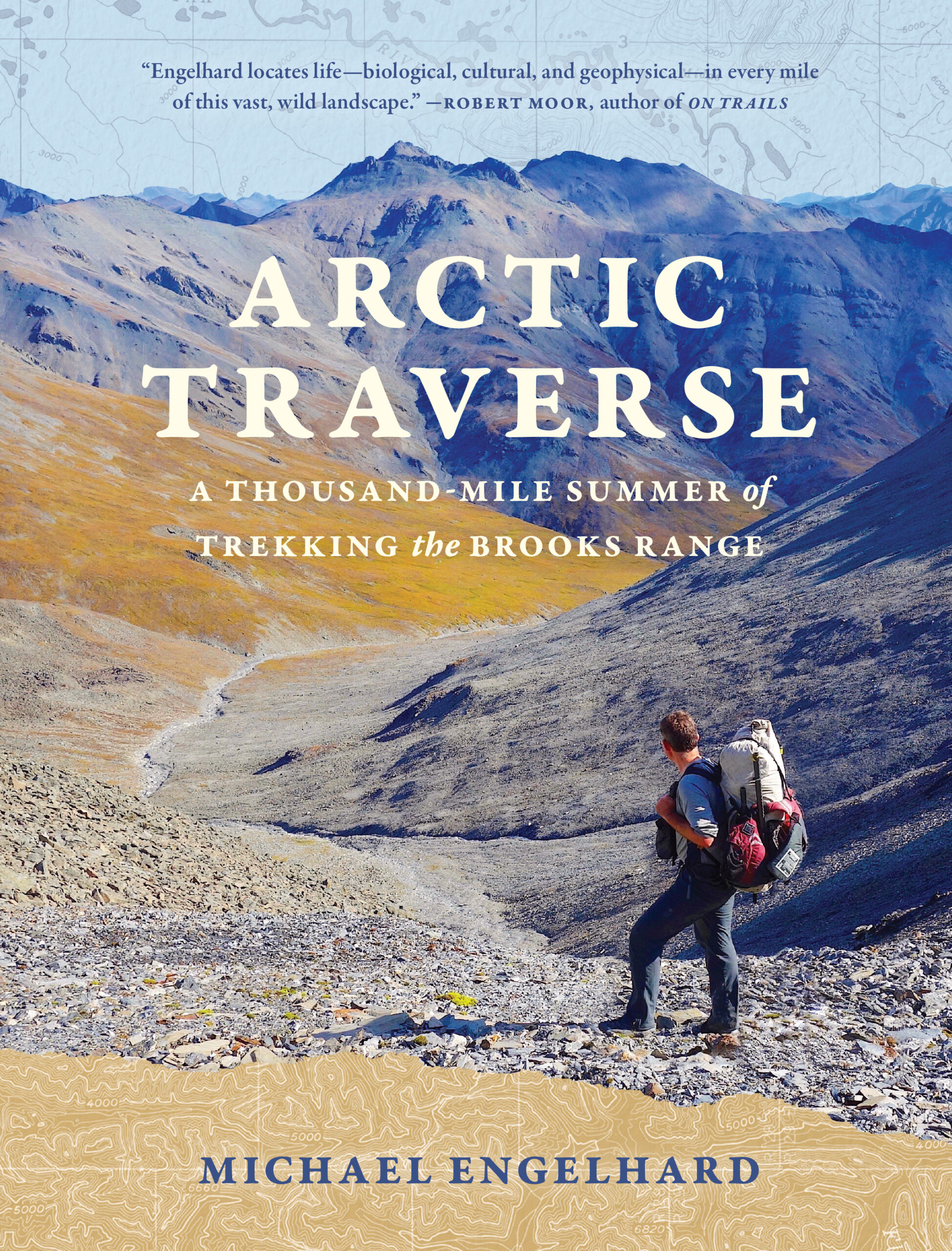

This is an adapted excerpt from the postscript of Arctic Traverse, Michael’s new book, available for purchase since April 1. When the book went to the printer, new insights into the mechanics of global meltdown—Earth’s chronic wasting disease—and news about its effects on the Far North had already surfaced.

My girlfriend, Melissa, saw me cross the tarmac in Nome when I returned from the endpoint of my traverse, Kotzebue, overdressed in my blue puffy coat, bushy bearded, with a thousand-mile stare. I’d descended the ramp stairs without too much trouble. At the luggage claim I seemed displaced and to shrink into myself. “How do we return home without breaking these threads that bind us to life?” Terry Tempest Williams asked after a visit to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. How do we stretch them to intertwine home? The novelist Murray Lee suggests that “those who have gone through great personal pain to escape society do not tend to function well when confined back to it.” Cultural disorientation upon reentry is real, lingering, and quite confounding, and the subject of many thru hikers’ blogs. The inner glow lasts for weeks but dims inevitably, in inverse relation to pounds regained.

Melissa gasped when I undressed for my first shower in two months—and not in a smitten way. “Gulag survivor,” she said, exaggerating, shocked perhaps. We had no bathroom scale, so I cannot provide a number, but when I sat down on the toilet it felt weird not just because of the flushing. There was no cushioning, no derriere there. I had not taken my clothes off in weeks, had slept in long underwear and not bathed; it had been cold and raining anyway and I was alone and soaked much of the time, so hygiene never became an issue. When I glanced in the mirror, I scared myself. Melissa had prepared a big dinner, and I stuffed my face as I would a woodstove on a cold day. Long after midnight, she heard the fridge door open and close, not once, but repeatedly.

More than a decade later, that 990-mile summer remains the best outdoor season of my life. I learned that extended solitude does not break me and that fear will not keep me from doing the things that matter to me. I am glad not to have missed the window my aging body is closing. Had I never done anything else, these weeks of silence and distance alone would have made it all worthwhile.

I keep writing about the Arctic beyond these pages you’ve turned, speaking up on the refuge’s anniversaries or when some idiocy threatens the Brooks Range. Bob Marshall, still overly stuck on northern Alaska’s importance for humans, valued it for “the emotional values of the frontier,” the sense of discovery, freedom, and self-sufficiency that it preserved. Modern developers embrace a materialistic slant of the same legacy: economic opportunity, weak government regulation, and prosperity for the ruthless few.

The Ambler Access Project ballyhooed by a State of Alaska public corporation entails a 211-mile road through the south side of Gates of the Arctic that would lead to the development of a massive copper mine, a “resource,” in the official spin, “essential for . . . green energy products, and military effectiveness.” This Haul Road spur would not only carve up and pollute an ecosystem that six wild and scenic rivers water but also harm wildlife, especially the Western Arctic caribou herd. Villagers, though not all, oppose this latter-day stampede the state labels a “path to opportunity.”

After a lengthy permitting process, the scheme by 2022 had reached the phase of preparatory fieldwork when the Interior Department, believing the environmental analysis to be awed, halted it. It will resume when the Washington pendulum swings to the right again.

Or even sooner. After ConocoPhillips posted record profits yet again and scientists announced that global heating would exceed 1.5° C, the Biden administration, breaking yet another pre-election promise, approved the Willow Project on the North Slope, one of the country’s largest oil and gas developments, in its largest still untrammeled tract.

It’s like a tragic, dirtier Groundhog Day.

News headlines break my heart over and over again. Worldwide, one of ten faunal species will be gone by 2100. Mere nostalgia has bled into solastalgia, the grieving for places irrevocably lost, lost not to creaky memory but to development and its apocalyptic horse- and henchmen. On a positive note—I hear you must finish on one if you care to retain readers, as nobody likes a downer—the Arctic Refuge and Gates of the Arctic endure in much of their terrific splendor. Adaptation and evolution proceed, evidenced in recent grizzly–polar bear hybrids (“grolars” or “pizzlies”) and in beavers engineering the tundra.

Caribou of the Porcupine herd in the Arctic Refuge. Danielle Brigida, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Still, an Arctic warming four times faster now than the rest of the globe breaks even the most sophisticated climate models. Trees growing ever farther north during longer summers shrink tundra habitat and may sentence some species to extinction. Like excessive snowfalls, forests insulate soils currently thawing, preventing refreezing in winter, which could cancel out the additional sequestering of carbon dioxide in the wood’s biomass. A historical drop in trapping could swell the surge of northbound beavers, which in Northwest Alaska advance five miles per year on average. Already, their stick dams, easily counted on satellite photos, distend south-slope Brooks Range and Kotzebue-area creeks into wetlands, which speeds up permafrost decay by decades: a waist-deep pond can warm bottom muck fifty degrees Fahrenheit above the ambient air temperature. James Roth, a UAF ecologist, never expected beavers on the North Slope, yet he estimates that by the second half of this century, they’ll be settling there. Fishes and insect larvae will live in ponds they create, which are deeper and do not freeze solid.

The author Jon Waterman, a former guide on the Noatak, in 2021 floated part of that river thirty-six years after his last visit. He faced August temperatures approaching 90 degrees for three days running and mosquitos “strangely thick.” As he correctly observed, night frosts should have killed most by then. Throughout the range, meanwhile, some streams have turned cloudy, rust-orange, and so acidic they curdle powdered milk, tainted by degrading permafrost, scientists speculate.

Civilization’s mission creep in the high latitudes, the changed seasons and vegetation, the loss of species and silence, of clean water and contemplation, won’t be outright clear to the next generation, which inherits all this. You could argue that I contributed through my writing and guiding and lifestyle, though the largest group I ever led numbered five—a High Peaks all-women backpacking trip—and I remain child- and carless. In the so-called “developed world,” we’re all implicated in the main dilemma of our era, the fallout from the Anthropocene. It is crucial that we curb our appetites, humbly make amends, and start to take drastic measures.

Unlike that Las Vegas deal, what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic.

About the author: Traveling by foot and raft, anthropologist and award-winning author Michael Engelhard has crafted a lyrical portrait of Alaska’s northernmost mountain range rich with reflections on history, culture, conservation, and the idea of home. Respect for the land and its inhabitants have shaped his exploration of this incomparable place. Follow him through tussock-studded tundra for a remarkable tale of bear encounters and white-knuckled river moments as he realizes a long-held dream in an untamed region. Drawing on the knowledge of scientists and Indigenous elders and on conversations with guided clients, Engelhard shines a light on the spirit of Alaska.

A veteran wilderness guide and recipient of a Rasmuson Individual Artist Award, Michael Engelhard is the editor and author of several books, including Ice Bear, No Walk in the Park, and What the River Knows.