Where late the sweet birds sang

A guest post from author and professor K. Brenna Wardell, who was raised in Southeast and south central Alaska, primarily on the Kenai Peninsula.

By K. Brenna Wardell (Cover photo via Derrek Faber)

“Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang” was written prior to the COVID-19 crisis; however, posting it now feels fitting as this is a moment when many of us have the chance to experience greater quiet and, in some cases, additional time to notice the presence, aural and visual, of birds and other living beings.

That is certainly the case for me. With less traffic on the road I hear the calls of my neighborhood birds more clearly, from the smooth whistling songs of the cardinals, the males’ vivid scarlet feathers dazzling my eyes, to the harsh rattling sounds of the Carolina wrens, sending out the alarm at the sight of a neighborhood cat. Walking away from the deserted downtown recently, I saw four turkey buzzards feeding on a possum corpse; as I strode around the eerily blank streets on another day, I looked up to see a heron sailing high above, heading for a nearby creek. Unmoored in this strange, unsteady time, I’m grateful for the liveliness of bird sounds and sights and of everything I too-often take for granted.

______________________________

In the opening of The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer’s late fourteenth-century poem about a group of pilgrims journeying to Canterbury Cathedral whilst telling stories, the poem’s narrator introduces his audience not to the pilgrims, as one might expect, but to the world in which they travel. It is an April world of fresh showers, soft west winds, and blooming flowers brought alive by Nature’s quickening pulse of spring. To these luscious sights, smells, and references to the tactile, the poet adds sound: “And smale fowles maken melodye/That sleepen al the night with open ye/(So priketh hem Nature in hir corages)” (lines 9-11). Roughly translated into contemporary English, the lines read, “And small birds make melody/That sleep all night with open eyes/(So pierces them Nature in their hearts).” Through these opening lines the poem’s audience members are immediately immersed in a world of the senses, hurtling into Chaucer’s particular vision. From the birds’ and countryside’s awakening, the scene then moves to the pilgrims assembled at the Tabard Inn in London’s Southwark, waiting to set off on their pilgrimage and reveal their stories.

For the pilgrims, as for the poem’s original listeners or readers, the sounds and sights of birds would have been a reminder of a world arising from the stark landscapes and stilled sounds of winter into a spring of green promise, a time to be busy and joyful. These songs might also have been a reminder of the music that would greet the pilgrims at their journey’s end — the music of the Cathedral’s choristers raising their voices, the sounds swelling amidst the carved wood of the choir stalls, rising up past the vast stained windows and swirling around the vast stone ceiling.

This potential connection between the birdsong of the countryside and the sweet human song of the choristers becomes a central image centuries later in William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73, in which the poem’s speaker, feeling aged and broken, speaks to his younger lover. Describing his own decay, he compares himself to trees shivering in the cold, their branches barren except for a few leaves, trees that become “Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.”

For Chaucer and Shakespeare, the birds and their songs are a reminder of spring and spiritual seeking, a pulse of youth and energy — even if only a remembered one. For other artists, birds have been at different times harbingers of peace, danger, threat, or contrition. These representations range from the Spirit of God imagined as a dove brooding over the universe and creating life in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, to that of the albatross in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner — the helpful spirit who is shot down by the mariner and whose death becomes a curse upon the mariner’s fellow sailors and their voyage.

A sinister note is provided by the ominous dark shapes in Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds — once-gentle creatures who are menacing the inhabitants of a small town for no discernible reason, their very ubiquity a promise of unending woe. These images and attendant ideas about birds have, like birds themselves, become such a part of our cultural imagination that we accept, often dismiss, them unthinkingly — rarely considering their import in our daily lives.

Many of my memories, including some of my first ones in my former home state of Alaska, are filled with birds: the tiny hummingbirds at the red plastic feeder on a warm summer afternoon; the blue-jays knocking on the windows to wake us up to feed them; the eagles riding the breeze, seemingly casually, watching for a loose chicken from our coop; as well as the small songbirds I watched on visits to my grandmother’s house in Yorkshire, an ever-moving cluster of bright blue and yellow shapes gathering to feed on crumbs on the thick stone still of her kitchen window.

During long Alaskan winters I’d sit by our log fire and watch the chickadees feed off wild cranberries, their tiny dark and pale heads bent over the red berries, and in the spring there were the robins in the garden and the seagulls on the beach. Most miraculous of all these birds to me were the snow geese, who would visit the mudflats in the spring on their long migration north. The sight of them wheeling round and settling on the mudflats, turning the flats’ brown expanse to a moving snowy sea of white, amazed me each year I saw it. I miss those sights now, living so far from home.

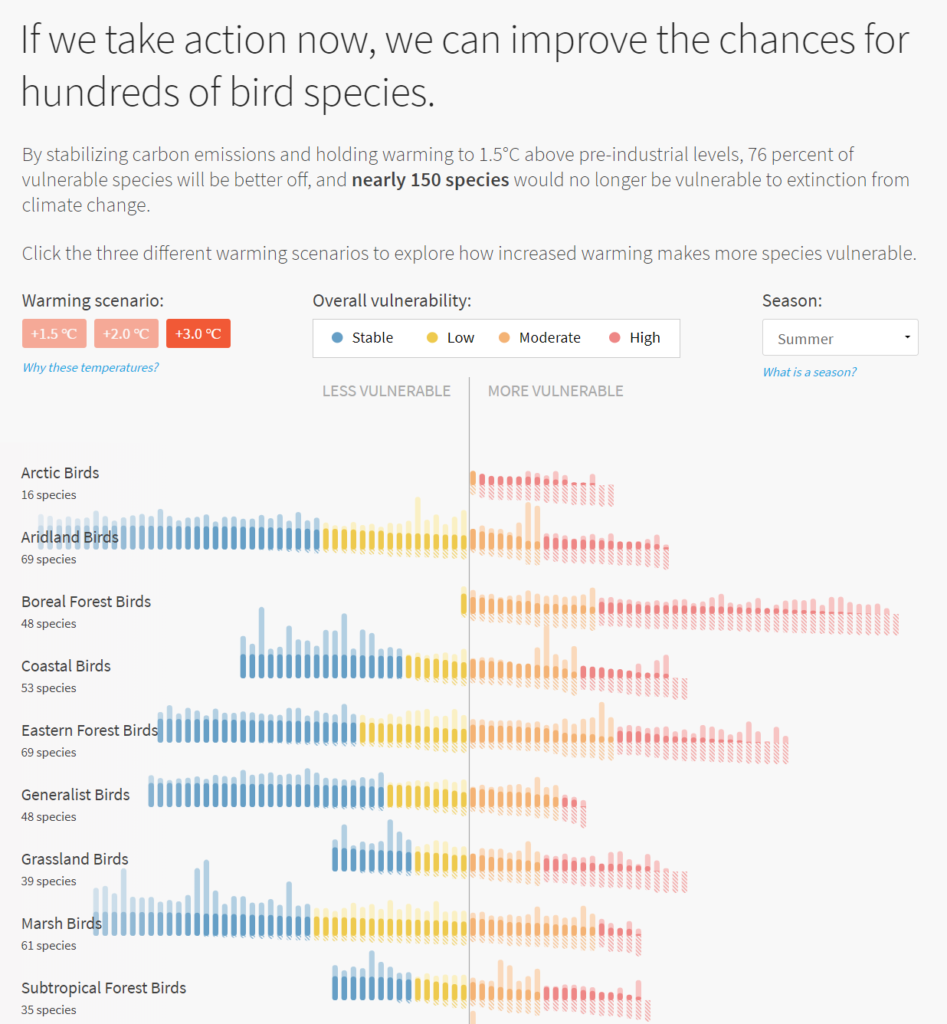

I wonder how future artists will imagine birds — the sight, touch, sound of them — from the echoing clap of pigeons rising from the ground to the soft calls of a cardinal chick summoning its parents or the haunting whistling song of the golden-crowned sparrow, with its sweet-mournful call of “Oh, poor me,” the background as I did chores around our home in Kenai, Alaska, or walked the Resurrection Pass Trail, further up the Kenai Peninsula. I wonder about this because our birds are disappearing. According to the National Audubon Society — founded by the naturalist John James Audubon, who created some of the first images of American birds in his book Birds of America (1827-1838) — birds in the United States are increasingly negatively impacted by human activity, from direct alteration of their habitat to the environmental shifts of climate change. The study argues that more than half of these birds may be lost; the global impact will probably be similar, or worse.

What will it mean to no longer see a robin in the spring, its red breast shining amidst the fresh new grass, or to be unable to draw our eyes away from the mundane to gaze at hawks spiraling high above, riding the air in a manner that we can only dream of doing? Without the birds some insect populations may thrive even as others wane, providing not just a nuisance but a significant health issue, and the ecosystem will be even more damaged, imperiling the existence of all creatures. And there will be no sounds to greet us when we venture outside except the mechanical shrill of machines — no liquid glissandi, soft trills, or aching notes falling away into silence: how poor we will all be then.

K. Brenna Wardell was raised in Southeast and south central Alaska, primarily on the Kenai Peninsula, where she grew up cross-country skiing, fishing, showing goats and horses, and working on the slime line in local canneries. She currently lives in Alabama, where she is an assistant professor of film and literature at the University of North Alabama. She is the author of a collection of poems and short stories titled “Of Moose and Me: Animal Tales from an Alaskan Childhood,” published in 2019 by Corpus Callosum Press.

You can read about her creative and academic work on her website.