The Gwich’in and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

A fight against oil development in the Arctic.

Alaska Wilderness League is proud to share student work focused on wild Alaska, its people and its wildlife. For more stories like this from the next generation of advocates, check out the “Next Gen“tag! Find the original version of this story here.

Cover photo: Gwich’in leaders and advocates with the Representative Deb Haaland (D-NM), now Interior Secretary Haaland, protesting oil development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Alaska Wilderness League)

By: Brianna Sherer

Alaska is known as a place where the last truly wild landscapes in the United States can be found. It is here that magnificent areas of public lands like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge have been created, however, the history of the original stewards of these places is oftentimes forgotten or ignored. Public lands in the United States have been created by the removal and displacement of Indigenous people. This statement is also true for the Gwich’in people of Alaska and Canada, who today must fight to preserve their culture and food sovereignty against large oil companies in the Arctic.

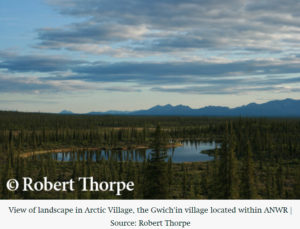

There are two distinct Indigenous groups that consider Arctic Refuge to be their traditional lands; they inhabit two villages within or along the boundaries of the refuge. The Gwich’in of Arctic Village oppose fossil fuel development, and the Iñupiat of Kaktovik are in greater support of it. The media attention that covers the Arctic Refuge controversy often depicts this issue to be the fossil fuel industry versus environmentalists, with very little regard to the advocacy of the Gwich’in Nation, who have for decades successfully protected this area to which they are indigenous.

The Arctic Refuge is one of the largest wildlife refuges within the U.S. Its total area is approximately 19 million acres, equivalent in size to the state of South Carolina. The ecosystems of the Arctic are critical and highly sensitive environments. The Arctic Refuge was originally established in 1960 by President Eisenhower to “preserve unique wildlife, wilderness, and recreational values.” In 1980, President Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), which created the Arctic Refuge as we know it today. Section 1002 of ANILCA established a 1.5-million-acre plot of land along the Arctic Ocean coastline called the coastal plain, also referred to as the 1002 Area. ANILCA left the coastal plain in a legislative limbo, granting the authorization of oil and gas development to a future Congress.

The Arctic Refuge is one of the largest wildlife refuges within the U.S. Its total area is approximately 19 million acres, equivalent in size to the state of South Carolina. The ecosystems of the Arctic are critical and highly sensitive environments. The Arctic Refuge was originally established in 1960 by President Eisenhower to “preserve unique wildlife, wilderness, and recreational values.” In 1980, President Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), which created the Arctic Refuge as we know it today. Section 1002 of ANILCA established a 1.5-million-acre plot of land along the Arctic Ocean coastline called the coastal plain, also referred to as the 1002 Area. ANILCA left the coastal plain in a legislative limbo, granting the authorization of oil and gas development to a future Congress.

The coastal plain is the most contentious area of the Arctic Refuge, where disputes between fossil fuel developers and the Gwich’in originate. The sensitive ecosystem there serves as the primary calving ground of the Porcupine caribou herd, upon which the Gwich’in people rely for food and around which their culture revolves. The Gwich’in people refer to the 1002 Area as “the sacred place where life began,” or “Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit.”

The Arctic Refuge and its coastal plain are home to the most diverse wildlife in the Arctic. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Arctic Refuge is home to at least 42 fish species, 37 land mammal species including the endangered polar bear, eight species of marine mammals, innumerable numbers of insects, and more than 200 species of migratory and stationary birds (USFWS 2013).

As stated before, the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge serves as the primary calving grounds for the Porcupine caribou herd, which the Gwich’in rely heavily on for subsistence hunting and survival. Biologists, including Mike Suitor of Environment Yukon, say that the area is a “vital component to the health of the Porcupine Caribou” and that any disruption to this area would “cause harm to the herd” (Fox 2017). There are two major herds of caribou that migrate to and inhabit Arctic Refuge: the Porcupine and the Central Arctic caribou herds. In a study conducted from 1983 to 2001 on the Porcupine caribou and 1980 to 1995 on the Central Arctic caribou, researchers were able to map the migratory and breeding habits of both herds within Arctic Refuge. Researchers discovered that the epicenter of the annual range, major calving sites, and the entire extent of calving grounds were located in the heart of the coastal plain, exactly where oil drilling and development have been proposed (Griffith et al. 2002). Subsistence activities such as hunting, gathering, and fishing are all vital to the survival and cultural integrity of the Indigenous people that thrive in these areas. This connection to and reliance on the land and animals of the refuge means that oil drilling in Arctic Refuge would be a threat to Gwich’in human rights and food security. According to the Gwich’in, the destruction of the caribou calving grounds would be considered a form of cultural genocide.

As stated before, the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge serves as the primary calving grounds for the Porcupine caribou herd, which the Gwich’in rely heavily on for subsistence hunting and survival. Biologists, including Mike Suitor of Environment Yukon, say that the area is a “vital component to the health of the Porcupine Caribou” and that any disruption to this area would “cause harm to the herd” (Fox 2017). There are two major herds of caribou that migrate to and inhabit Arctic Refuge: the Porcupine and the Central Arctic caribou herds. In a study conducted from 1983 to 2001 on the Porcupine caribou and 1980 to 1995 on the Central Arctic caribou, researchers were able to map the migratory and breeding habits of both herds within Arctic Refuge. Researchers discovered that the epicenter of the annual range, major calving sites, and the entire extent of calving grounds were located in the heart of the coastal plain, exactly where oil drilling and development have been proposed (Griffith et al. 2002). Subsistence activities such as hunting, gathering, and fishing are all vital to the survival and cultural integrity of the Indigenous people that thrive in these areas. This connection to and reliance on the land and animals of the refuge means that oil drilling in Arctic Refuge would be a threat to Gwich’in human rights and food security. According to the Gwich’in, the destruction of the caribou calving grounds would be considered a form of cultural genocide.

Gwich’in Protest

The Gwich’in have protested development of the 1002 Area primarily in three ways: by advancing legislation; by creating partnerships with major companies such as Patagonia to raise awareness; and by filing lawsuits against companies that attempt to drill within the 1002 Area. In June 1988, members of the Gwich’in Nation traveled from their communities throughout Alaska and Canada to Washington D.C. in response to the proposal of oil drilling in Arctic Refuge. Soon after this protest, the Gwich’in Steering Committee was established. A statement from the Gwich’in Steering Committee reads:“

“Our elders recognized that oil development in caribou calving grounds was a threat to the very heart of. our people. They called upon the chiefs of all Gwich’in villages from Canada to Alaska to come together for a traditional gathering – the first in more than a century. At the gathering in Arctic Village, we addressed the issue with a talking stick in accordance with our traditional way and decided unanimously that we would speak with one voice against oil and gas development in the birthing and nursing grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. Our unified voice is expressed in a formal resolution, Gwich’in Niintsyaa.” (Gwich’in Steering Committee n.p.)

Since its establishment, the Gwich’in Steering Committee has continued to raise awareness of the Arctic Refuge controversy, highlighting the fact that it is an issue of human rights and food sovereignty to the Gwich’in. Members of the steering committee have testified in front of Congress, at the United Nations, and at public hearings throughout Alaska. The Gwich’in and the steering committee have reframed the controversy over Arctic Refuge and are challenging “a long colonial history of Indigenous exclusion and erasure from public lands” (Dunaway 2021 n.p.). The Gwich’in have turned this fight into a fight for environmental justice.

A second major victory for the Gwich’in took place in response to the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act. Signed by President Trump on December 22, 2017. This act included the intention to sell land within the 1002 Area. The Gwich’in and their allies, led by the Gwich’in Steering Committee, responded with lawsuits towards the Trump Administration. They also launched a corporate campaign that targeted oil companies and financial institutions, pressuring various companies to not invest in Arctic Drilling.

According to an article in the Washington Post, this divestment campaign played a critical role in “steering Big Oil away from the lease sale” (Dunaway 2021). Through this form of protest, the Gwich’in were able to successfully deter major banks in the U.S. and Canada from funding drilling in the Arctic, further protecting Arctic Refuge. These efforts also made it so that the attempted sale of land in the 1002 Area on January 6, 2021, the same day as the insurrection at the Capitol Building, was embarrassingly unsuccessful. According to an article published by National Public Radio, the lease sale only attracted three bidders and generated a small percentage of the revenue it was projected to raise; meanwhile, “half of the offered leases drew no bids at all” (Hanlon and Herz 2021).

Today, the 1002 Area in Arctic Refuge is still open for bidding and development. Politicians, especially those in Alaska, continue to support fossil fuel development in the 1002 Area. With the election of the Biden-Harris Administration and Deb Haaland as head of the Department of Interior, there is new-found hope for the protection of the Arctic. In January of 2021, President Joe Biden signed an executive order place a “temporary moratorium on oil and gas activity in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge” (DeMarban 2021). This moratorium does not place any permanent protections on Arctic Refuge quite yet, but it is a step in the right direction and shows that this administration may do a better job than its predecessors in listening to Indigenous voices. Until then, it is a waiting game to see what decisions are made regarding this controversy. No matter what happens, however, it is certain that the Gwich’in will not give up their fight to protect their lands, human rights, and food sovereignty.

Brianna Sherer is originally from Anchorage and the Native Village of Napaimute, Alaska, and is currently a junior at Fort Lewis College, Colorado, where she is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Studies along with minors in both Wildlife and Ecological Biology and Native American/Indigenous Studies. As a final project for her Indigenous Environmental Movements class, she chose to write about the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the efforts of the Gwich’in people to protect their lands and traditional way of life. As someone who is Indigenous to Alaska, Brianna feels it is important to share her stories and to serve as a voice against extractive companies exploiting our people and lands.

Further Viewing:

Works Cited:

“Biden blocks drilling in ANWR, among his first acts as president,” Anchorage Daily News (January 20, 2021) https://www.adn.com/business-economy/energy/2021/01/20/biden-plans-to-block-drilling-in-arctic-refuge-shortly-after-taking-office/

“Indigenous advocacy transformed the fight over oil drilling in the Arctic Refuge,” The Washington Post (March 14, 2021) https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/03/14/indigenous-advocacy-transformed-fight-over-oil-drilling-arctic-refuge/

“‘This Fight Is Not Over:’ Gwich’in, Environmental Groups Vow to Resist ANWR Oil-Drilling,” Fm.kuac.org (December 22, 2017) https://fm.kuac.org/post/fight-not-over-gwich-environmental-groups-vow-resist-anwr-oil-drilling

“Developing Alaska’s Wildlife Refuge Would Increase US Crude Oil Production after 2030,” EnergiMedia (June 15, 2018) https://energi.media/usa/development-alaska-wildlife-refuge-increase-crude-oil-production-2030/

“Threat of drilling in ANWR a long-fought battle for Gwich’in, environmentalists,” Yukon News (October 19, 2017) https://www.yukon-news.com/news/threat-of-drilling-in-anwr-a-long-fought-battle-for-gwichin-environmentalists/

“Keepers of a Way of Life,” (November 26, 2019) https://www.patagonia.com/stories/keepers-of-a-way-of-life/story-74969.html

“Canada-United States Agreement on Porcupine Caribou Herd Conservation,” Government of Canada (February 26, 2015) https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/corporate/international-affairs/partnerships-countries-regions/north-america/canada-united-states-porcupine-caribou-conservation.html

“Section 3: The Porcupine Caribou Herd,” U.S. Geological Survey: Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain Terrestrial Wildlife Research Summaries (January 2002) https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/bsr20020001

Gwich’in Steering Committee. “Caribou People.” (Accessed April 18, 2021) https://ourarcticrefuge.org/about-the-gwichin/caribou-people/

“Major oil companies take a pass on controversial lease sale in Arctic Refuge,” National Public Radio (January 6, 2021) https://www.npr.org/2021/01/06/953718234/major-oil-companies-take-a-pass-on-controversial-lease-sale-in-arctic-refuge

Public Land Order 2214: Establishing the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1960) https://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/Region_7/NWRS/Zone_1/Arctic/PDF/ANWR_plo.pdf

——— 2012: “Timeline: Establishment and Management of Arctic Refuge – Arctic – U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” October 15, 2012. https://www.fws.gov/refuge/arctic/timeline.html

——— 2013: “Wildlife & Habitat – Arctic – U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” Updated Nov. 5, 2013. https://www.fws.gov/refuge/arctic/wildlife_habitat.html

——— 2014: “Management of the 1002 Area within the Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain – Arctic – U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” February 12, 2014. https://www.fws.gov/refuge/arctic/1002man.html

——— 2019: “Facts and Features – Arctic – U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” September 18, 2019. https://www.fws.gov/refuge/arctic/facts_and_features.html