Finding yourself in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

March 6, 2020

This piece originally appeared in Hi Travel Tales. For more on author Michael Hodgson, check out his Amazon page here.

By Michael Hodgson

I stood at the edge of nothing and saw everything. Atop a rocky outcropping in Sunset Pass in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, I gazed out over an almost unimaginable expanse, a pristine landscape uninterrupted by roads, buildings or any trace of human existence. The undulating carpet of green was laced with ribbons and pools of water, each reflecting the early evening sun and sparkling like diamonds tossed from the hand of God. The scene, framed by distant mountains where the rivers and streams began flowing, was a snapshot in the middle of one of the last bastions of unspoiled wilderness in the world.

How a former Republican representative, keen on arguing in favor of oil and gas exploration could, in 2012, refer to this place as nothing special, “a moonscape” devoid of wildlife and plants, was beyond me. In just a week, I had walked over endless mounds of tundra grass and through scattered thickets of willow, laid down in the middle of dense fields of fragrant lupine, and waded through acres of marshes and bogs. I’d seen wolverine, grizzly, caribou, fox, and I’d almost stepped on a wolf – yeah, you read that right. I can assure any doubter that the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (Arctic Refuge) is very much alive, and for now, quite well.

Thanks to a summer sun that dipped to caress the horizon but never set, I squeezed every last ounce out of my week, stopping my wanderings only to eat and catch a few hours of sleep. The more I saw, the more I realized I needed this place even though I may never be fortunate enough to visit it again. We all need ANWR, just the way it is and always has been.

What is the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge?

Standing in Sunset Pass, I have only felt this same intensity of emotion and connection to our earth once before – when, as a much younger man, I stood at the edge of the Rift Valley in Kenya. Perhaps this is why the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is sometimes referred to as America’s Serengeti. It is also known simply as ANWR (pronounced “an-wahr”) or Arctic Refuge.

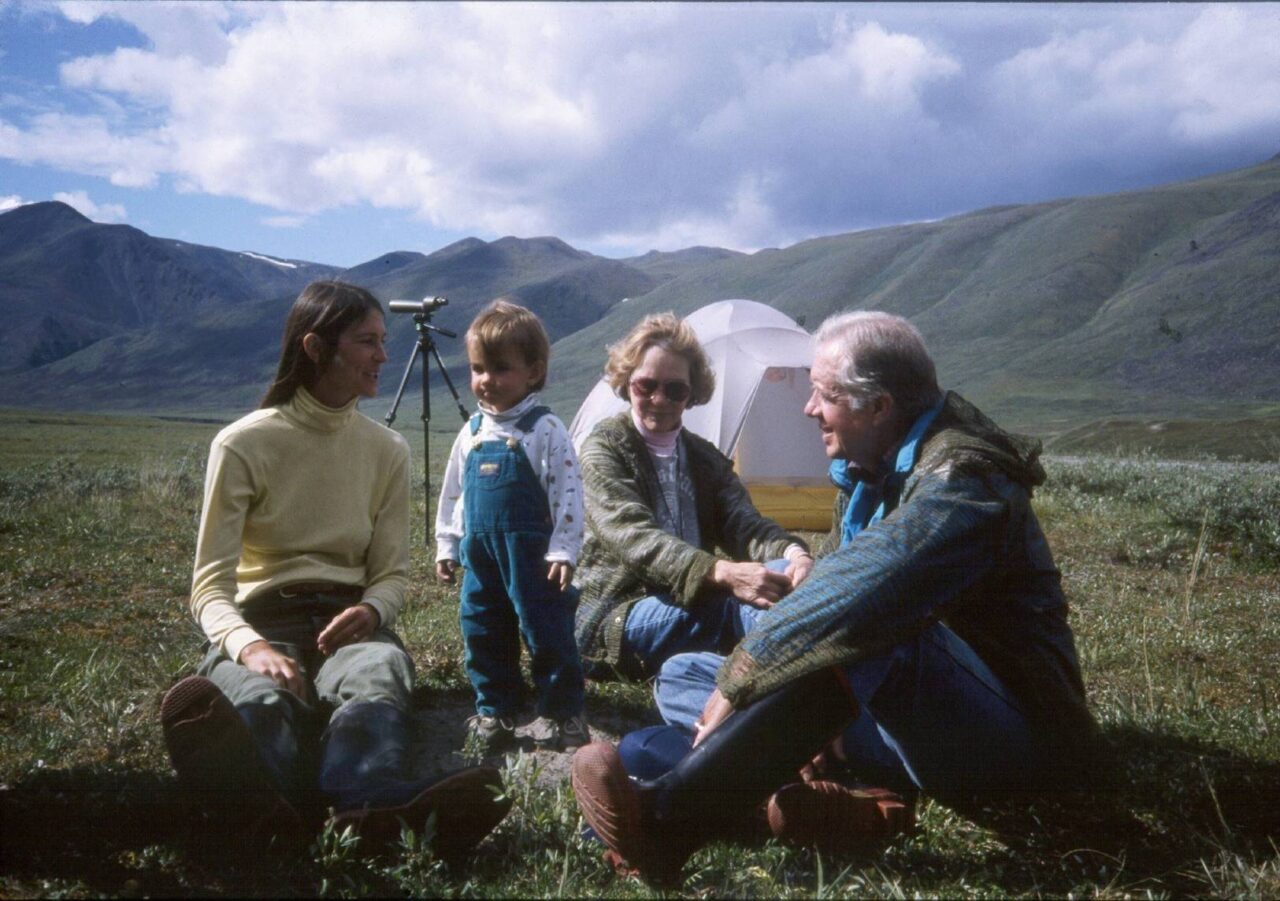

Located in northeastern Alaska, the refuge as we now know it was expanded and much of it protected as wilderness by President Jimmy Carter in 1980. However, the Coastal Plain, the 1.5-million-acre biological heart of the refuge, was left unprotected from future oil and gas development, leaving it up to Congress to either open the area up for drilling, or protect it forever. In 2017, a Republican-led Congress enacted legislation to open the Arctic Refuge to drilling, although lawsuits and significant public opposition have stalled the efforts thus far.

The Arctic Refuge covers 19.3 million acres and represents one of the largest intact ecosystems anywhere in the world. It remains, for now, untouched and unblemished by human development, existing as it was hundreds upon hundreds of years ago. No roads. No transmission lines. No buildings. No oil rigs. No pipelines. Home to 37 species of land mammals, eight marine mammals, 42 types of fish, and more than 200 migratory bird species, the refuge is also the calving grounds for the Porcupine Caribou herd which currently numbers around 197,000. The 1,400-mile migration of the herd is one of the world’s great natural events. ANWR is also part of the ancestral range of the Gwitch’in people, and they view the caribou as their main source of subsistence as well as a spiritual and cultural treasure for local communities.

The Gwitch’in people refer to the coastal plain in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as “The Sacred Place Where Life Begins.” If mining and drilling are allowed in this place, it could be where life for much of the refuge ends.

The land where life begins indeed. A nest of baby birds near our Canning River camp. (Michael Hodgson)

Standing on a wolf

Dirk Nickisch of Coyote Air dropped off our small group alongside the Canning River for the first of our two basecamps. The plan was to spend several days exploring the Canning River area before Dirk would pick us up again and fly us to our second basecamp location in Sunset Pass. It was on a misty first morning at our Canning River camp that I saw my first wolverine – bounding across a distant snowfield and then onto a rocky slope above camp.

This was also where I almost stepped on a wolf: I had left our group sitting by a lake above camp so I could wander across a bog and then follow the banks of the Canning River back toward our campsite. I had wandered alone for just over an hour when I arrived at a high embankment overlooking a bend in the river. A carpet of lupine spread out on all sides of me. Naturally, I did what any self-respecting travel journalist would do at that point – I took a selfie. Me in a blue hoodie to ward off mosquitos, with a magnificent, colorful backdrop. As I snapped the first photo, a very large, furry object leapt out from the embankment directly underneath my feet.

Me, in full selfie-mode, moments before the white wolf erupted from the ground beneath my feet. Yes, that is a mosquito by my head. (Michael Hodgson)

The furry object materialized into a beautiful white wolf, now standing not more than 10 feet away facing me warily. As its deep dark eyes stared into mine no other thought crossed my mind than to capture what was certainly going to be the photo of a lifetime. Sure, I only had an iPhone in my hand, but the wolf was right there. I took the photo, realizing as I did that I was, you guessed it, still in selfie mode. I switched back to rear camera mode quickly, but by then, the wolf had decided he didn’t care much for Instagrammable moments, and was already loping off.

A blurry image of the white wolf is the only photograph I managed sadly — not my finest moment as a travel photographer. (Michael Hodgson)

I watched the wolf run off, filming as it ducked behind the grassy hummocks of the bog, reappearing periodically to glance at me before climbing up and then disappearing over the ridgeline. Curious, I looked over the edge of the bank and quickly realized I had literally been standing a foot above an undercut in the embankment where the wolf had decided to rest.

I took a longer route back toward camp, hoping against hope to see the wolf again. It was not to be. I have a memory that will last for a lifetime. But, I admit it, a photo would have been nice too.

Just don’t get killed

It was on our third day in Sunset Pass, the day before Dirk would return in his aircraft to take us back to civilization, and I asked our guide from Arctic Treks Adventures if I could head out on my own. She understood my desire to spend a day exploring alone and acknowledged I was skilled and experienced enough to head out by myself. But she did leave me with one essential bit of advice before I shouldered my daypack, “Just don’t get killed.”

No doubt there is a lot that can go wrong very quickly for the unprepared, inexperienced, and inattentive explorer seeking to find adventure in the Arctic Refuge. Sudden storms, dangerous river crossings, unforgiving terrain. Oh, and grizzly bears. Though magnificent to see, grizzly bears are notoriously unpredictable and to be given a very wide berth. While I was carrying a mandatory bear repellent cannister, I didn’t want to test its effectiveness.

I walked swiftly away from camp, keeping as close to the side of the valley as possible to make walking easier. Though upon first glance the valley appeared grassy and open, it only took a few steps before one realized the terrain was actually a giant maze of grassy tussocks. These tussocks are made up of a type of sedge grass that grows in closely packed mounds, with each mound often surrounded by water or bog-like muck. Walking becomes a series of leaps, bounds, and stumbles taking much longer and far more effort to navigate even a few hundred feet than imagined. Staying high on the valley side amid loose rocks also took a bit of effort but far less so than tussock hopping.

To my right were rocky escarpments I had explored yesterday. They invited further wandering, but with only a day left, I chose instead to head up a draw that promised a sighting of at least a few caribou – a sighting that had eluded our group so far. We had hoped to catch a glimpse of the enormous Porcupine Caribou herd moving through or toward Sunset Pass, but thus far we’d only seen a few tracks and some droppings, likely from smaller groups that had broken away from the main herd.

It was unseasonably hot. Sweat drenched my insect-repellent hoodie, but I didn’t dare take it off. Whenever I paused for a look around and to listen to the sounds of birds or the gurgling water from a nearby creek, mosquitoes swarmed all around me. Wind thankfully blew steadily up the draw the higher I climbed, providing a cooling sensation and a bit of natural mosquito deterrent.

Three heads had already lifted from grazing and were staring right at me as I crested a plateau. They saw me before I was fully aware of their presence since the wind likely carried my scent right up to them. Three bull caribou — one much larger than the others and more splendidly antlered — were no more than 100 meters away. They returned to grazing as I crouched down, trying to stay as still and as quiet as possible as sweat ran into my eyes and mosquitoes began buzzing around my head in swarms.

Then all three heads suddenly lifted, this time looking up the draw to one side of the saddle above us. My gaze shifted up toward the ridgeline, too, and my heart skipped a beat. A large grizzly, now silhouetted against a blue sky, was clearly sniffing the air several hundred meters above us, likely trying to sort out the various scents the wind was carrying up to him — of caribou and me. It rocked back and forth in the saddle, at one point standing up on its hind legs. “Just don’t get killed…” whispered a little voice in the back of my head. The three caribou were already fast-tracking across the draw and now making an exit below me. I turned to watch them go for only a second or two, glancing quickly back to determine what the grizzly was going to do next, but as suddenly as it had appeared, the grizzly had vanished. At least it was not charging down the draw, which I took as a positive sign. But not knowing which direction the grizzly had gone, or if it was simply moving to come in around me from above was a bit disconcerting. I needed high ground. I needed out of this draw.

I shouldered my pack quickly and headed off in the opposite direction of the caribou, walking as resolutely and as smoothly as I could up a steep scree slope toward the rocky knife-edge above me. My goal was to move out of the confines of the draw and away from the saddle itself where the grizzly had last been seen. Once I gained high ground, I would have a clear view of anything large and furry with fangs and big claws that might have designs on turning me into an hors d’oeuvre. I am not sure if my heart was pounding from the effort of climbing, or the adrenaline of seeing a grizzly so close. Probably a little of both, although surprisingly I felt amazingly calm.

I reached the knife-edge of the ridge quickly enough. The caribou were long gone below me. I relaxed. No sign of the grizzly in any direction. From here, a cooling wind was now blowing strongly enough that even mosquitos were no longer an issue. I scrambled along the ridgeline toward the saddle where my intention was to walk toward what looked like an amazing view of the coastal plain. No mosquitos. No grizzly. Amazing views. Life was good.

As I climbed up onto a large flat boulder near the summit to sit for a while, I came face-to-face with a very fresh pile of bear scat. Only one bear could have left that marker. How the hell did he get up here without me seeing him? I looked around in all directions. Ahead lay the saddle. I could see the saddle clearly, but not what lay just on the other side of it. I could also see a clear route off the ridge I was on, steeply down and then up onto another distant, more rounded ridge, in the opposite direction of the saddle and a potential bear encounter. The decision was easy. I headed off.

Listening point

After an hour of hiking and a bit more scrambling, I was far away from the saddle. I was now on a windswept grassy ridge, carpeted with thousands of wildflowers. Lupine, wild sweet pea, arctic poppies, phlox (I think). The lupine were dense and fragrant. In a nod to one of my favorite naturalist authors, Sigurd Olson, and a man who also lent his voice to protecting the Arctic Refuge, I found a listening point where I could sit for a while and look out over the vast coastal plain below. From this same vantage point I had only to turn my head to see Sunset Pass valley below and the yellow dots of our tents in the distance. I was so very far from my home in California, and yet at the same time, I felt a part of me taking root here.

“Only when one comes to listen, only when one is aware and still, can things be seen and heard.” – Sigurd Olson, Listening Point.

Wind blew the grasses in waves as the late afternoon sun began to paint the land in an almost unreal golden color. Grateful for the absence of mosquitos because of the wind, I closed my eyes, laid back in the grass, and let my nose drink in the intoxicating scent of lupine. My ears became attuned to various birds (I am afraid I don’t know which species) chirping and singing nearby. Rays of sun washed over my body as the earth seemed to reach up and put its arms around me. Morning, when I had first left camp and my companions, felt so very long ago although only nine hours had so far elapsed.

“Without a love of the land, conservation lacks meaning or purpose, for only in a deep and inherent feeling for the land can there be dedication in preserving it,” wrote Olson in his book, Reflections from the North Country.

Ours had been a quick courtship. In just six days, I had fallen in love with the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. I have been asked many times since what I love so much about the place. Everything I say. It is the raw nature of the place. It is the spiritual power of the place. It is the unchanged wild spirit of the place. It is one of the last places on earth where we, as a human species, can experience a world that remains as it once was, still pristine, pure, alive. In the Arctic Refuge, you can feel the heartbeat of the earth I tell anyone who will listen. And yet the true value of this place is not found in anything really tangible.

Olson wrote, “When we talk about intangible values remember that they cannot be separated from the others. The conservation of waters, forests, soils, and wildlife are all involved with the conservation of the human spirit. The goal we all strive toward is happiness, contentment, the dignity of the individual, and the good life. This goal will elude us forever if we forget the importance of the intangibles.”

Looking back

“Here still survives one of Planet Earth’s own works of art. This one symbolizes freedom: freedom to continue, unhindered and forever if we are willing, the particular story of the Planet unfolding here,” wrote former National Park Service biologist Lowell Sumner in the 1950s. Sumner is credited as being one of the voices that led to the founding of the refuge.

I thought about that quote from my seat in Dirk Nickisch’s de Havilland Beaver as we climbed skyward, our former camp and Sunset Pass slipping below our wings. I could see the rocky outcropping where days before I had marveled at the bejeweled expanse. I thought back to my encounters with the bear, the wolverine, the wolf, and the caribou. I smiled at the memory of a midnight rainbow in camp, the result of a brief but refreshing thunderstorm.

In one respect, the Arctic Refuge is timeless. To visit feels a bit like stepping into a real-life Jurassic Park. Roads, vehicles, permanent structures, mining, logging, oil and gas exploration – they have no place here. Though it might appear a vast, empty nothingness to the casual observer, it is anything but. I invite you to spend some time in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Because when you do, I promise, you’ll see everything too.