Reimagining Aldo Leopold’s “The Land Ethic”

Alaska Wilderness League supporter Michael W. Shurgot, PhD, a retired Professor of Humanities from Olympia, WA, submitted this piece on Aldo Leopold, considered by many to be the father of wildlife ecology and the United States’ wilderness system. For more on Aldo Leopold, visit www.aldoleopold.org.

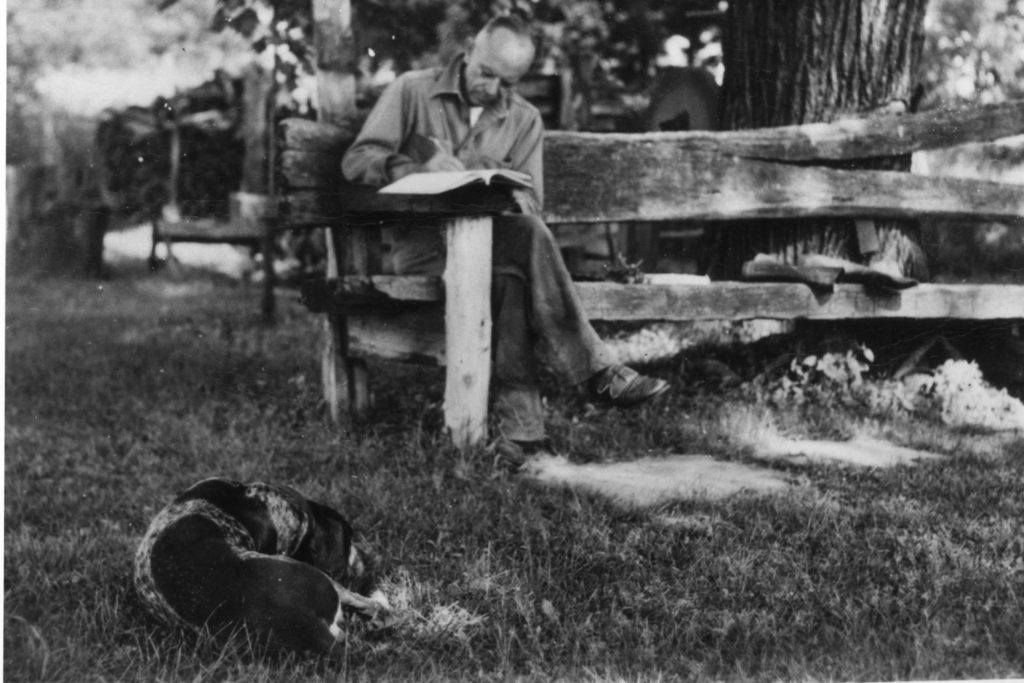

(Above: Aldo Leopold writing near Baraboo, Wisconsin, with his faithful friend Gus. Photo courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation.)

By: Michael W. Shurgot, PhD

During its initial two years in office the Trump administration has launched unprecedented attacks upon our environmental laws. Former Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt eviscerated laws governing the operations and emissions of coal plants and opened new coal leases on federal lands. Even more disturbing, Pruitt ordered the EPA to wipe information about global climate change from its website, as if hiding scientific information invalidated it. Ryan Zinke, former Secretary of the Interior, vowed to open America’s Arctic and vast tracts of the American West to oil and coal leasing, and attempted to slash millions of acres from National Monuments in Utah that are sacred to Native Americans and treasured by the majority of Americans for their scenic beauty and ecological integrity.

These actions are designed to increase profits for the energy and transportation sectors while derailing competition from green energy sources. Together these policies potentially mean more energy extracted from the planet, more severely damaged landscapes, and more air pollution for a planet already threatened by climate change.

The scale of this administration’s ignorance demands a response, and I suggest it lies in a renewed awareness and appreciation of Aldo Leopold’s The Land Ethic, a seminal essay in the history of the American environmental movement. The Land Ethic is the final essay in Leopold’s wonderful A Sand County Almanac (Oxford, 1949), a book that should be mandatory reading for every concerned American.

Leopold’s central vision reverses the biblical command to “go forth and conquer,” which he rightly sees as inherently and immensely destructive, and places humanity squarely in the midst of a reciprocal relationship with the natural world. Leopold asserts that, “A land ethic changes the role of Homo Sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it.” It implies respect for his fellow-members, and respect for the community as such. This sentence is both ecologically radical and entirely sane, because it emphasizes what we should realize but often, to our peril, ignore: that when we devastate our ecology, we jeopardize our own existence.

Applying Leopold’s criteria specifically to Scott Pruitt’s or now Andrew Wheeler’s policies at EPA, or the development schemes of Ryan Zinke or his successor at Interior David Bernhardt, yields obvious conclusions. Destroying mountain tops in West Virginia and pristine valleys in Wyoming to extract coal is wrong because mining and burning coal degrade land and air. Allowing increased mercury emissions from power plants is wrong because mercury damages the brains of fetuses and infants. Lowering MPG requirements is wrong because burning more fuel means emitting more pollution. And drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge or mining coal in Utah’s Bears Ears or Escalante Staircase Monuments is grotesquely wrong because such extraction activities violate intact wilderness for minimal coal or oil production while permanently scarring the landscape. Damning rivers without providing for salmon survival, as has happened all up and down the west coast of the United States, destroys not only the natural ecology of rivers as well as their fish runs, but also disrupts and often eliminates tribal and commercial fishing opportunities. Alternatively, solar and wind energy are right because green energy sources electrify buildings and automobiles without destroying the land or fouling the air.

Leopold’s simple yet profound thesis, and his challenging insight into humanity’s relationship with the environment is as crucial, if not more crucial, to the survival of the natural world today than it was when he wrote it in 1949. Americans need to rediscover Leopold’s brilliant essay and to re-imagine its profound importance in these troubling times.

Michael W. Shurgot, PhD, retired as Professor of Humanities from South Puget Sound Community College in Olympia, WA in 2006.