Here Be White Bears: The Arctic’s Pale Predators

Author Michael Engelhard has written essay collections including American Wild: Explorations from the Grand Canyon to the Arctic Ocean, and Ice Bear: The Cultural History of an Arctic Icon, from which this essay has been excerpted. He lives in Fairbanks, Alaska and works as a wilderness guide in the Arctic. This article has also appeared in Hakai magazine and is reprinted here with permission. See Michael’s prior post here.

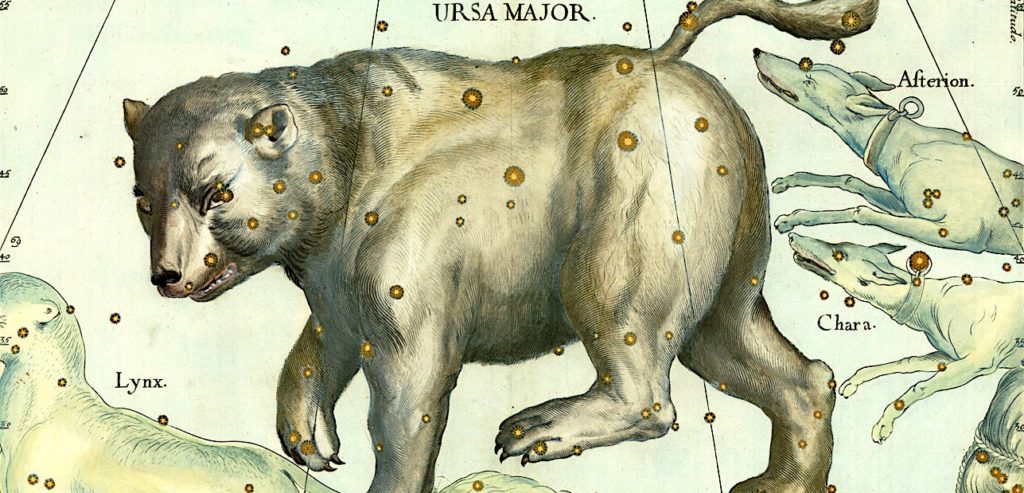

(Above: A celestial chart from 1687 is one of many illustrations from books, charts, and maps showing artists’ imaginings of polar bears.)

By Michael Engelhard

IN THE REPERTOIRE of Renaissance cartographers, fierce mythical beasts – from sea serpents to manticores – represented dangers of unknown worlds. Rather than “here be dragons,” one early terrestrial map of the Arctic warned that “hic sunt ursi albi” – here are white bears. Rarely seen and poorly understood, the pale predators signified the Arctic’s challenges to the world.

As men ventured into the Arctic, they returned home with stories of this mysterious creature. Bolstered by the invention of the letterpress, interpretations of the white bear began to appear in print. Painstakingly compiled from hearsay, travelogues and existing charts, these first images often contained substantial errors, which were then copied. Mapmakers sometimes let their imagination run rampant. Abhorring a vacuum and trying to boost sales, they populated empty spaces on their sheets with creatures that were part fancy, part sailors’ yarns. In an early version of the party game telephone, mistakes were compounded with exaggerations ever more outlandish.

The region’s name itself pays homage to a northern bear. The Greek root “arktikos” refers to lands that, when viewed from the Mediterranean, lie below Ursa Major, the Great Bear. In the 1687 celestial chart by Johannes Hevelius, the Great Bear has a longer tail than the real animal to accommodate the constellation.

The 16th-century scholar and archbishop of the Swedish town Uppsala, Olaus Magnus, was famous for his Carta Marina, a splendid map of northern Europe published in Venice, Italy, in 1539. Typically, Renaissance maps were printed in black and white and hand-colored at the behest of their owners, not by the publisher, and existing copies can therefore have different color schemes. Books, similarly, were sold as loose sheets to be bound and hand-decorated as the buyer saw fit.

Though Magnus clearly labeled the bears on the Carta Marina as ursi albi, artisans who finished copies of the map colored them according to their own whims, sometimes in the more familiar brown of European bears. The Carta Marina’s three bears are most certainly polar bears, however, since no brown bears lived in Iceland (Islandia). The inland bear is portrayed inside a cave or den, although polar bears most likely never hibernated in Iceland. Only pregnant females of this species truly hibernate, but, historically, Iceland never had a breeding population.

In his 1555 travel guide “Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus” (Description of the Northern Peoples), Magnus describes hunters donating white bearskins to the high altar of Trondheim cathedral in Norway, “so that during a period of dreadful cold the celebrant priest should not suffer frozen feet.” The bearskins probably came from Iceland or northern Norway. One of the bears on Magnus’s map, an image recycled to head a chapter in “Historia,” shown here, chews on a fish. Tellingly, that chapter is titled “De Ursis Piscantibus,” or “Of Fishing Bears.” This foraging mode was, and still is, believed to be common, though polar bears mostly hunt seals.

A 1590 map of Iceland by the Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius – who was also the first person to intuit continental drift – explains how polar bears got to Europe’s second-largest island, and still do: on sea ice floating southward and eastward from the pole, skirting Greenland’s north coast. The map’s legend provides details: “Huge and marvailous great heaps of ice brought hither with the tide from the frozen sea, making a great and terrible noise; some pieces of which oft times are fourty cubites bigge; upon these in some places white beares do fitte closely.” Although Icelanders quickly killed most of the marooned bears because they threatened their sheep flocks, they occasionally captured and traded orphaned cubs, or gifted them to European royalty, to be kept in private menageries.

Polar bear fossils and bones have been found far outside the species’ present range. They have come from the Aleutian Islands and the Bering Sea’s Pribilof Islands, from Scandinavia, and even the British Isles. In 2004, a fossilized polar bear jawbone 110,000 years old was excavated from a coastal cliff in Norway.

Medieval and Renaissance texts and map legends also yield some important clues to the animal’s historical range. In about 1075 CE, for example, the monk Adam of Bremen mentions white bears as far south as Norway in “Descriptio insularum aquilonis” (Description of Islands in the North). Norway is the only place that has “white weasels and bears of the same color, who live in the water,” he wrote.

Conceivably, during Europe’s Little Ice Age, polar bears were crossing the ice pack to mainland Europe or drifting ashore on the continental mainland at the same time as they did in Iceland. It seems that a demand for live cubs and polar bear skins or a shift in climate led to the animal’s extermination in mainland Norway.

Statements about white bears in northern Norway can also be found on Angelino de Dalorto’s 1339 portolan, shown above, and on several later maps. Portolans are navigational charts used in the late Middle Ages that showed only ports and coasts in detail. As an emigrant from coastal Italy to Majorca, Spain, Dalorto cared more about port towns and marine highways than their terrestrial equivalents. “Here are the white bears and they eat raw fish,” he remarked about Norway. Dalorto imagined Norway as a square, as shown here outlined in brown, and the text referencing polar bears sits just north of it. Unfortunately, no animal image comes with the annotation.

With the dawn of the age of exploration, especially the pursuit of an elusive shipping passage through the Arctic, Europeans routinely encountered polar bears on the animals’ home ground. Initially, such voyages sought to open trade routes to Japan and the Indian Ocean. Later, they became quests for national prestige, strategic pursuits or rescue missions for missing crews.

Already in 1492, when Christopher Columbus embarked for the Indies, the German mariner and cosmographer Georg Martin Behaim had blazoned an animal that might be a polar bear near the North Pole of his 1492 Erdapfel (earth apple) globe. On an island resembling Greenland, an archer faces this white enigma. A reproduction of the globe’s design shows the animal with a long tail, similar to a wolf’s. The often repaired and revised original globe at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, however, depicts it without a tail, which would make it a polar bear.

The first image of a polar bear in North America proper adorns a world map from 1544, usually ascribed to the Venetian Sebastian Cabot. The son of an explorer, Cabot first chased the Northwest Passage funded by merchants and later in the service of Spain and England. His map has the Arctic Circle at the approximate latitude, and two bears just south of it, in what today is northern Quebec, Canada. “The land is very sterile. There are in it many white bears,” a handwritten comment on the map reads. The bears, with their tongues lolling, seem to be either salivating or panting.

Pierre Desceliers’ sprawling and teeming 1550 mappamundi, or world map, positions fish-eating bears in Labrador, eastern Canada. Desceliers belonged to a group of chart makers in Dieppe, France, who broadcast French and Portuguese conquests in the New World through their maps. The color of these bears is off, but a few clues indicate they are most likely polar bears. First, the area is treeless tundra into which eastern Canada’s grizzly bears rarely, if ever, venture. As well, two of the three bears frolic on ice floes, which grizzlies reportedly never do.

The unknown helper who colored the map likely remembered bears he’d seen or simply chose gray and brown because they better contrast with a white background. One of the few convincing suppositions about polar bears fishing comes from Labrador’s White Bear River. There, in 1775, the English fur trader and adventurer Captain George Cartwright found thousands of fresh fish carcasses and polar bear tracks, good evidence of their behavior in the territory’s extreme southern parts.

With a growing body of knowledge from whalers and walrus hunters sailing the Arctic, depictions of the more northerly latitudes and their inhabitants became increasingly accurate. However, the newer maps also reveal distortions. In a cartouche on the Dutch atlas maker Willem Janszoon Blaeu’s map Regiones Sub Polo Arctico from circa 1635, the dress, weapons and faces of two Indigenous hunters suggest Ottomans and might have been modeled on these “savage” archers. Their polar bear counterpart appears wolf-like.

Regiones Hyperboreae is a pole-centered 1616 map by the Flemish theologian, historian and cosmographer to the court of Louis XIII, Petrus Bertius. Its bear in the margins rears up on hind legs – a most impressive posture – and, like the walrus, is rendered realistically compared to the map’s whale, reindeer and wolf or Arctic fox. While biological knowledge gained from captive white bears had improved, the Arctic’s geography still held big secrets. On the Bertius map, a polar sea rumored to be ice-free year-round lies enclosed by a landmass dissected by four narrow channels. This fiction endured. In 1860, the American physician Isaac Israel Hayes tried to break through a bulwark of pack ice in search for this open stretch. And as late as 1913, the American Museum of Natural History sponsored an expedition to find Crocker Land, a huge island Robert Peary claimed to have sighted in 1906, but which did not exist.

Even this narrow cartographic slice from 1,100 years of contact between Europeans and polar bears shows that the white bear has meant different things to different people. Across cultures and time, its remoteness invited projection, and we eagerly saddled it with our fears, fantasies and ambitions. Like the blank spots on explorers’ maps, it forever keeps us guessing its true nature – and that of the no-longer-so-unknown North.